Searching Semantic Roles is Awesome in Logos 6 #Logos6

Last week I wrote a post about exploring meaning using case frames in Logos 6. I plan to come back to that topic with more practical examples in the near future, but I also wanted to introduce you to the semantic roles data on its own terms by taking a look at how these roles have enhanced clause search. By the end of this post, I think you will agree with me that this dataset is, quite frankly, awesome.

First, a brief aside: the case frame data that I talked about in the last post is made up of the semantic roles data. The important point here is that you can approach this data by looking at case frames as units of analysis or by individual semantic roles as units of analysis. If that doesn’t make sense at this stage, it’s not so important, but it may help to know that the case frames and semantic roles are interrelated.

Now I will inductively work through an example that I think will demonstrate just how exciting this new feature is. Imagine for a moment that we want to find all of the places in the Bible that talk about Jesus being baptized. In the past, we might have tried to accomplish this by using clause search and the grammatical categories of ‘subject’ and ‘object.’

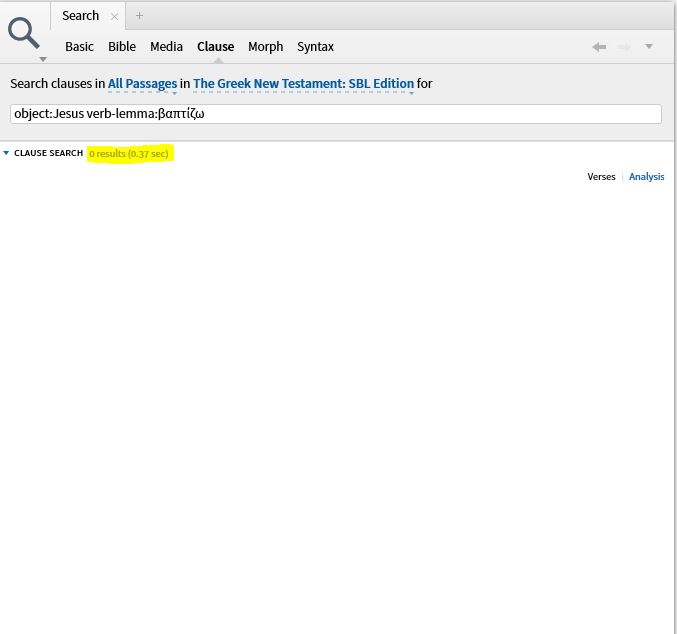

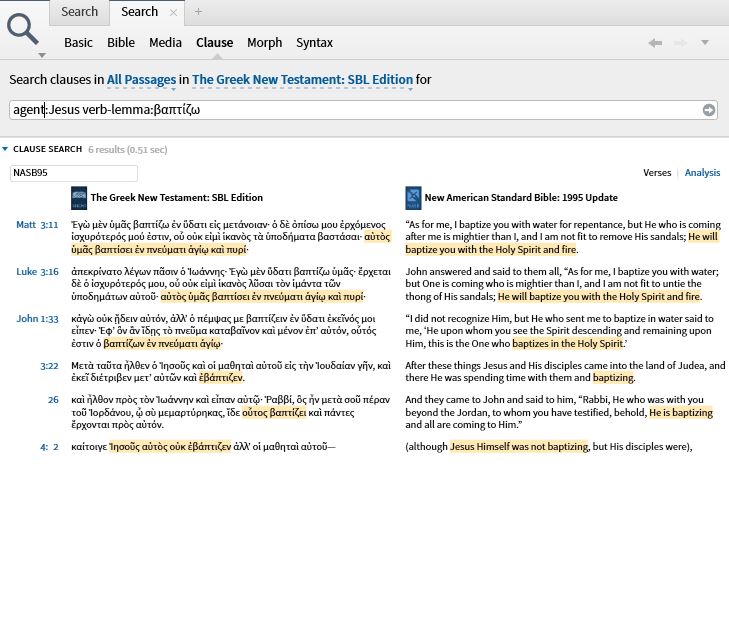

First, we might think: John the Baptist (subject) baptized Jesus (object). So, our first search might be something like “object:Jesus verb-lemma:βαπτίζω.” Let’s check out the results of this search:

Nothing.

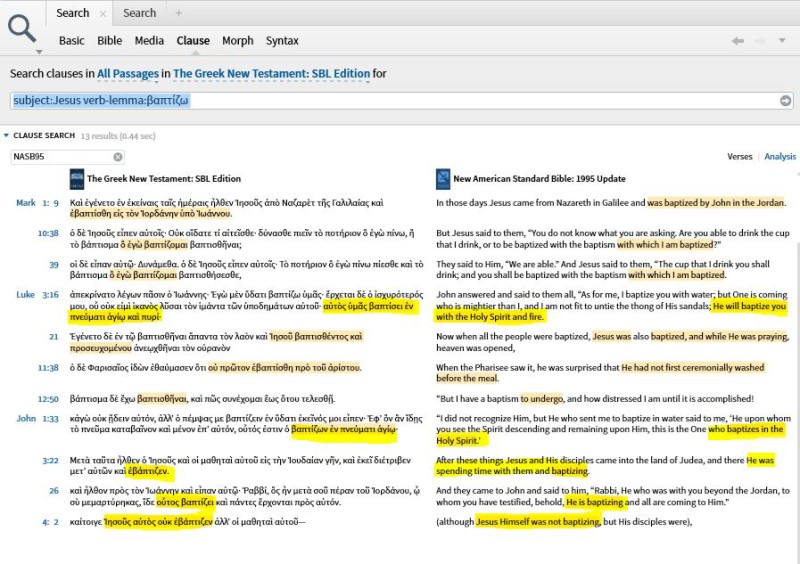

What’s the issue? … We forgot to take into account the passive voice. Maybe all of the cases of Jesus being baptized are more like: Jesus (subject) was baptized by John. Our next search might end up as “subject:Jesus verb-lemma:βαπτίζω.” Here’s what we would find:

This is obviously better; however, we’ve still got some noise in our search. We’re seeing instances that mention Jesus actually doing the baptizing. Is there a better way to do this?

If we think briefly about the semantic roles for βαπτιζω, it is possible to find a better way. A look at the semantic roles for βαπτιζω tells us that the person being baptized in each case is a “Theme.” With that little bit of knowledge, it is possible to search by meaning (i.e., semantics), as opposed to grammatical categories like subject and object that don’t always overlap completely with meaning.

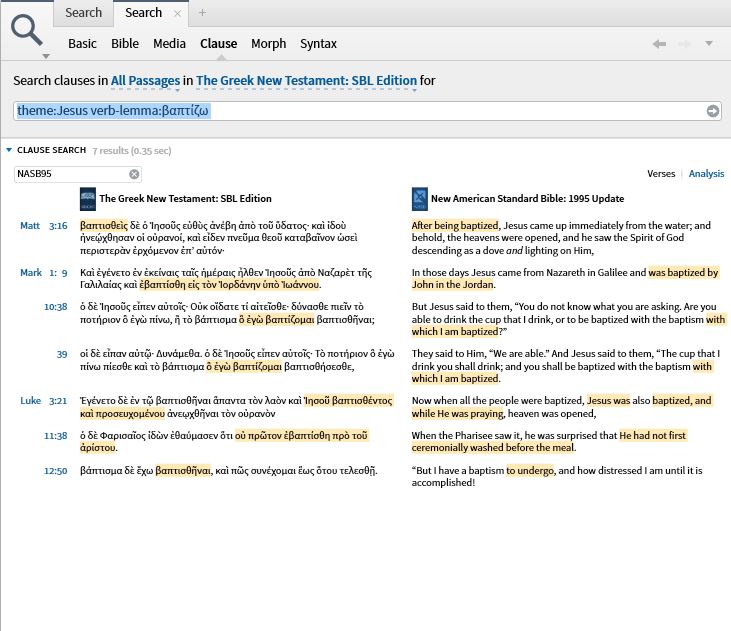

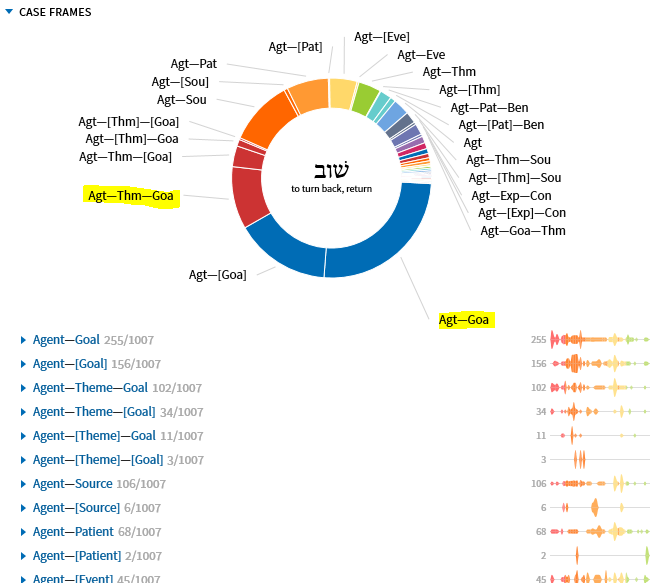

If the previous paragraph was too much to parse, don’t worry about it because I think the next example search will make it easier to understand. What if we were to try “theme:Jesus verb-lemma:βαπτίζω”? Here’s what we would find:

Jackpot! Take a look at the results. Now we’re seeing exactly what we want. But wait … there’s more. What if on the other hand, we wanted to find all of the places that mention Jesus doing the baptizing (for example, baptizing with the Holy Spirit)? Another brief reflection on the semantic roles of βαπτιζω would tell us that the person doing the baptizing is an “Agent.” Maybe we could try “agent:Jesus verb-lemma:βαπτίζω”:

Bingo! Our ability to search the Bible becomes so much more powerful when we are searching by meaning as opposed to searching by grammatical categories. I hope that this example has demonstrated that it is worth the time to get to know the semantic roles data because it could save you a lot of time in the long run.

So, go buy Logos 6 if you haven’t already! Then feel free to ask any questions about semantic roles here or in the Logos forums. Or, drop a cool example of how you’re using this tool in the comments below.

Explore Meaning with Case-frames in Logos 6 (Or, what I’ve worked on for the last year) #Logos6

Rick has already posted some of his favorite features in Logos 6. So, I thought I’d take some time to post on my favorite feature in Logos 6 while also mimicking his post title. Incidentally, I’m biased because I worked on the Hebrew data for this project. Paul Danove (whose work really inspired this feature) provided initial Greek data, and Mike Aubrey continued that work.

Case-frames provide a new way of exploring meaning within Logos 6. It may not be apparent on first glance how they do this. Here I will work from an English example to an original language example to demonstrate how this works.

Consider an English verb like “return.” This verb can have several different meanings as in the following sentences:

- He returned home.

- He returned the donkey to its pen.

In the first case, we might paraphrase “return” as “go back”: “He went back home.” In the second, we might somewhat poorly paraphrase as “bring back” (perhaps this isn’t the only possible interpretation, but this is only an example): “He brought the donkey back to its pen.”

The difference in these two meanings of “return” is reflected in the number of “arguments” that the verb takes in each example. I don’t want to get bogged down what an argument is, but it is linguistic unit (word, phrase, clause) that is required to determine the meaning of a verb (or some other kind of predicate). In the first example above, the verb has two arguments: someone (an Agent) who is going back somewhere and the place (Goal) to which the person is returning. The second example has three arguments: the person (an Agent) returning something, the object (a Theme) that is being returned, and the place (a Goal) to which the object is being returned. As hinted at above, these arguments are labeled with roles like “Agent,” “Theme,” and “Goal” in a case-frame analysis. A fuller discussion of each one of these roles can be found in the glossary of semantic roles in Logos 6.

An analysis of the arguments in the two examples above would look something like this:

- [Agent He] returned [Goal home].

- [Agent He] returned [Theme the donkey] [Goal to its pen].

The meaning of the verb “return” in the first example is reflected in the pattern Agent – Goal and the second meaning is reflected in the pattern Agent– Theme– Goal. Thus, the meaning of “return” is related to the construction in which it is involved.

Of course, every language has important differences. But, these underlying patterns also occur in a language like Hebrew (though in Hebrew the differences between the two meanings discussed above are also somewhat reflected morphologically – qal vs. hiphil – for those who know their Hebrew).

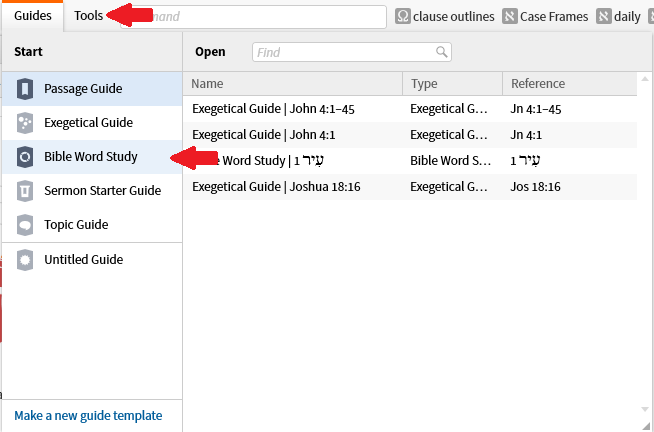

The Biblical Hebrew word most often rendered “return” by English translations is שׁוב (šwb). To see how we can explore the meanings of this verb by looking at its patterns like we did for the English examples the first thing we want to do is run a Bible Word Study. So open up the Bible Word Study guide:

Since this isn’t really a tutorial on how to work with Hebrew in Logos I’ll give you the easy version of how to search for our Hebrew word. In the top left search box we can enter “h:shwb” then select the appropriate Hebrew word from the dropdown:

Once the guide has finished gathering all of the necessary information make sure the “case-frames” section is expanded by clicking the arrow next to “case-frames”:

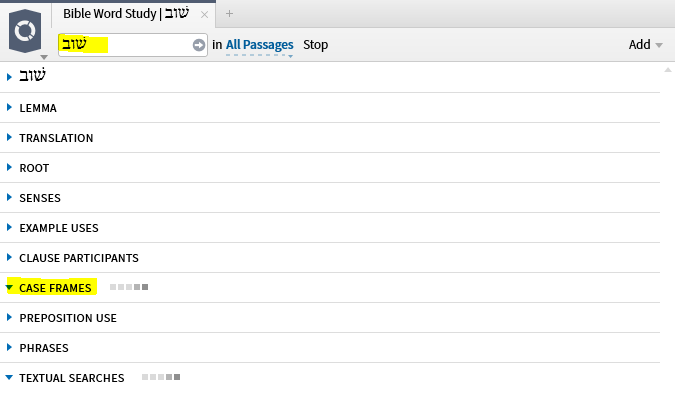

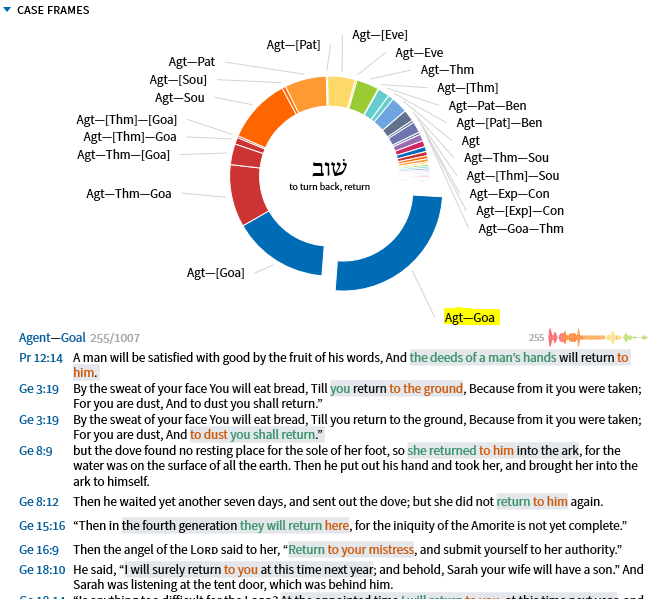

And now we can look for the patterns that we’ve discussed so far, which I’ve highlighted already. We can open up the search results for each one of these patterns by clicking on the appropriate section of the case-frame wheel. For the Agent – Goal pattern we see the following:

We notice right off that case-frames can either be abstract (“the deeds of a man’s hands will return to him”) or concrete, and we see concrete examples of the Agent– Goal pattern, such as Gen 8:9 “… [Agent she] returned [Goal to him] … “ and Gen 15:16 “… [Agent they] will return [Goal here] …” Again, these examples approximate the English example of “He returned home” that we looked at above.

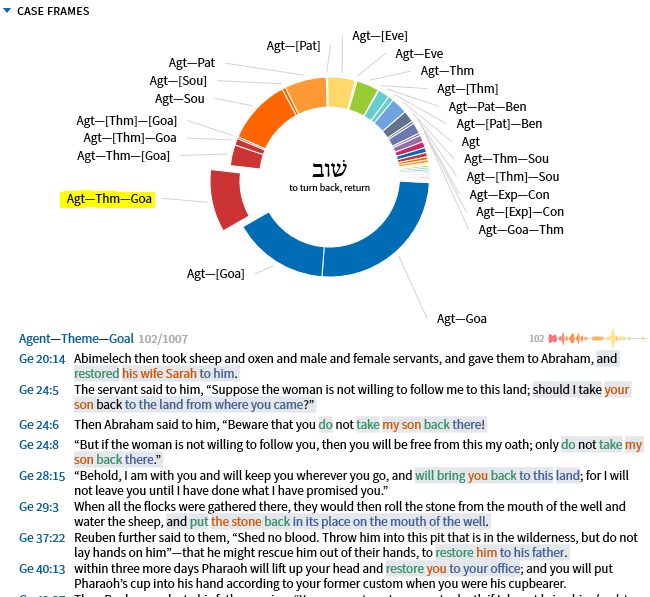

When we look closer at the Agent– Theme– Goal pattern we see the following:

One interesting matter to note here is that the translation generally doesn’t use the word “return,” so if we were just looking at an English translation we may have no idea that these usages were related to the same verb as the Agent – Goal pattern. Again, we have some abstract and some concrete examples. Concrete examples occur in places like Gen 29:3 “[Agent (they)] put the stone back in (i.e., return the stone to) its place on the mouth of the well” and Gen 28:15 “[Agent (I)] will bring you back (i.e., return you) to this land.” Again, these meanings of שׁוב (šwb) approximate the meaning we discussed in the second example above: “He returned the donkey to its pen.”

To summarize, we can see here how different meanings of verbs can involve different patterns of semantic roles. We particularly looked at the English example of “return” and how to look at similar examples in a language like Hebrew using the case-frames analysis in Logos 6. This was only an introduction using a common English example, but there is a vast amount of semantic information to explore here. And I’m pretty excited about that. So, go buy Logos 6! Then, explore the new case-frames feature and drop a comment below with a favorite example. And if you have any question about this feature or any other, please feel free to ask. If I know the answer, I’ll help the best way I can. And if I don’t know they answer, I’ll try to point you in the right direction.

McWhorter’s The Story of Human Language on Sale

Linguist friends, John McWhorter's The Story of Human Language from the Teaching Company is in the "buy one, get one" sale from Audible through tomorrow. FWIW, I picked it up along with Vonnegut's Hocus Pocus. If you're an Audible member, you can check it out through the link above.Must a person speak a language to understand it?

This is an important question to ask for instructors of ancient languages who want to move toward communicative approaches to language instruction, and the answer to this question is: no. This doesn’t necessarily rule out that we should use communication in ancient language instruction (though for this and a number of other reasons I wouldn’t), but it should at least mitigate the degree to which instructors insist on it for everyone.

One problem with the view that a person must speak a language in order to properly understand it, which we sadly learn about mostly from the misfortunes of people with language disorders, is that language production and understanding dissociate. In other words, different language problems can affect either production or comprehension. I was reminded of this while reading Gregory Hickok’s The Myth of Mirror Neurons shortly after writing my previous post which pertained to some extent with language instruction and understanding. Hickok describes at length the observations of Eric Lenneberg on one of his patients:

Lenneberg noted that the child’s ability to speak was effectively nil. The child cried and laughed normally but made only cough-like grunts that accompanied his attempts to communicate via pantomime. When he played alone, he often made sounds that resembled Swiss yodeling, although he had never been exposed to the art form. Lenneberg further noted that as the child got older, and after years of speech therapy, he could repeat a few words after his therapist or mother, but even these attempts were “barely intelligible” and were never produced on his own.

Lenneberg was fascinated by the boy’s ability to comprehend language, which the scientist characterized as “normal and adequate understanding of spoken language.” This observation was confirmed over more than 20 visits and by several doctors and speech therapists, both informally and formally. The boy could follow complex commands such as “Take the block and put it on the bottle” and he could appropriately respond, albeit nonverbally, to questions about a short story that was read to him. He was not merely cuing off the body language of the researchers: he accurately followed commands even when he couldn’t see the investigator. The cause of the speech production deficit could not be determined. Lenneberg called it “congenital dysarthia” – difficulty controlling the speech articulators – and concluded that the ability to master receptive language, to understand, did not depend on the ability to produce or imitate speech.

Dissociations between production and comprehension are also present in different kinds of aphasia (for good introductions to aphasia see Basso and Goodglass; Basso is probably the better of the volumes, but Goodglass is a little easier to read). Aphasias also differ in how they affect the ability to read. Yet Lenneberg’s patient and others like him demonstrate that a person can understand a language though they may never have been able to produce it. Of course, this should be taken with a bit of a grain of salt since, as I pointed out in my last post, a second language will never be the same as a first language. But, even working on that analogy, it does not seem to be the case that the ability to speak a language is a necessity for understanding it.

Reading a second language will never be like reading a first language

This post is in partial reply to one written by Daniel Streett. I should start off by saying that I applaud the efforts of all those attempting to make biblical language instruction better and to train better interpreters of the bible. Changes in biblical language instruction still have a long way to go and have been quite a long time coming.

Against that background, I think there are different paths that we could take to do that. So, I will offer here a differing perspective, which suggests reasons for a more positive role for a first language in the interpretation of a second language. I think this may logically lead to a more positive view of the first language in the instruction of the second language.

The main thrust of this post has to do with one of Streett’s* overarching analogies: We should try to read and understand Greek texts like we read and understand English ones. Perhaps more broadly, we should try to read second language texts like we read first language ones. The analogy comes out most clearly in his second to last and final paragraphs:

So, I find that the question, “what about exegesis?” presupposes that to interpret a text, one must be able to label, diagram and translate it into another language. I disagree with this. When I read and discuss English literature, I do not analyze syntax or diagram sentences. I also do not label each element using linguistic metalanguage. Rather I discuss meaning, themes, characterization. I summarize. I paraphrase. I make connections with other parts of the text. I tease out logical implications. I examine elements of literary artistry. All of this can be done, indeed, is best done, in the language itself.

To summarize, when you can read a language fluently, much of what we call exegesis becomes basically unnecessary.

At this stage, I should say that from an idealistic point of view I agree. In particular, aside from everything else I will say below, I do absolutely agree that much of what we call biblical exegesis is too atomistic. What I’m really dealing with here is the final two sentences in the quotation. From a realistic point of view, my feeling is that the strong form of what he saying is not possible. Reading a second language will never be like reading a first language.

In what follows, I will very briefly state why I think this is the case in hopes that this will point toward a more positive role for a first language in the understanding of a second. First, second languages are not stored in the brain in entirely the same way as first languages. Evidence for this can be found in the phenomenon of paradoxical aphasia. This phenomenon is discussed at length in The Neurobiology of Learning: Perspectives from Second Language Acquisition by Schumann, et al chapter 3 (I think this book is a must read for anyone working in the area of applied linguistics). In paradoxical aphasia, a first and second language are differentially affected by lesions or some other brain insult. This form of aphasia suggests that a first language relies more heavily on procedural memory and a second language a combination of declarative and procedural memory (the author of the chapter goes on to suggest that this along with other findings suggest that Krashen’s strong distinction between learning and acquisition, which is at the heart of many communicative approaches, is wrong and based on a faulty understanding of Chomsky’s concept of Universal Grammar that ignores the concept of critical periods; however, I will perhaps leave that for another time).

Second, we should ask whether the fact that different pathways are used for first and second languages has any psychological effects. Based on at least one line of very recent research that I’ve mentioned on this blog, though in light of the biological factors mentioned above I would predict that you could find others, this does seem to be the case. Some potential psychological effects might result from the second language not being as closely tied in with the emotional pathways in the brain. One particular example of this is that, on the description of the researchers involved in the study I just linked to, people are more “logical” when reading and reasoning about a moral dilemma in a second language than in their first language.

Some readers of this blog may want to brace themselves for one possible implication here if you haven’t already felt it: The irony is that if someone wants to feel more strongly the emotional impact of a biblical text, they might actually be better off reading the text in good translation … I know. I think I just vomited a little in my mouth. We do, indeed, need to place a strong emphasis on students learning biblical languages. I obviously think they are extremely important, else I would not have pursued a PhD in biblical languages. But alas, the biblical languages aren’t magic no matter how well one knows them. From the standpoint of a linguist, I have to be open to the idea that we might actually lose something by only reading and thinking about (I leave aside the whole debate about whether or not we actually think in a natural language) a text in a foreign language (unless you’re a Vulcan and think that more logic always should trump emotion). All meaning is constructed. A different kind of construction texts place when understanding a second language text due to the biological factors at work.

If you’re not quite ready to admit a strong version of what I said in the last paragraph that’s okay. I understand. And, this is a blog, so I’m only citing one study and leaving you to follow that trail out for yourself if you want to (I have a day job and blog very rarely by night). But, I’ll come back to the main point. Is the idea that we should try to understand a second language text by simply reading it just like, or even almost like, we would read a first language text a good analogy? Ideally, I would say yes. But realistically, I think the above suggests that this may not be possible and that statements like “All of this can be done, indeed, is best done, in the language itself” require some rethinking. This might include some rethinking about a more constructive role for a person’s first language in the understanding of a second language text. I think the exact role a first language should play is up for quite a bit of debate, but it’s a role I think is made necessary by the very biology of the learners that we may work with.

* I’m not trying to sound all academic or anything, I just don’t know him and don’t want to presume to call him Daniel.

Postscript: For those interested in information of a more practical sort (though perhaps less scientific since it would be impossible outside of a controlled environment to isolate the individual factors that have lead to its failing), you may be interested in looking into the recent reports about the failings of Rosetta Stone, an instructional software in which all instruction is in the second language. It has not lived up to its claims to such an extent that, to my knowledge, they have begun to lose their government contracts.

With lexicographers you really just never can tell

I hate Joyce’s Ulysses

I finally decided. I hate it. I think I understand why someone might like it. The stream of consciousness writing style mimics what is supposed to be going on in our own minds or some such, and that’s novel. Maybe even cool. Daniel Dennett even uses it as a metaphor for what consciousness is really like with his terminology of a “Joycean stream of consciousness” in Consciousness Explained.

The problems for me are twofold: First, my own stream of consciousness doesn’t stop just because I’m reading James Joyce. So, I’m dealing with two streams of consciousness. It’s too much. Second, my left hemisphere interpreter, or whatever, can at least construct some kind of coherent narrative out my own stream of consciousness. Maybe my interpreter is faulty, but I just can’t do that with Ulysses, perhaps for the sheer fact that it’s not what’s really going on inside my head.

So, if you like Ulysses, I’m sorry. Chastise me if you must. I hate it. I hate it so strongly that I felt I needed to write a blog post about it, which is not something I’ve been doing so very often over the last several months.

“Through my most grievious fault”

Since the most recent changes to the Roman Missal almost every Sunday we’ve been saying:

through my fault, through my fault,

through my most grievous fault; …

I’ve noticed that in our congregation almost everyone says “grievious” as opposed to “grievous.” I knew that sometimes speakers insert an “-i-” into words like “grievous” and “mischievous.” But, I didn’t realize that this was perhaps becoming the dominant way of pronouncing the word. My guess is that it’s probably on analogy with words like “devious” and “previous.” Has anyone else noticed if this is becoming the primary way that “grievous” is pronounced? Or, is this just a quirk of our congregation?